A-List Celebrity No. 6: The DOW CHEMICAL case

- Raquel Macedo Moreira

- Oct 8, 2024

- 5 min read

This article is part of the series A-List: The Celebrities of Arbitration Cases. A series delving into the most renowned cases that have shaped the landscape of international arbitration.

Parties: Dow Chemical (France), The Dow Chemical Company (U.S.A), Dow Chemical A.G. (Switzerland), Dow Chemical Europe (Switzerland) v. Isover-Sain-Gobain

Decided by: Arbitral Tribunal in the ICC Case No. 4131 (Pieter Sanders, Berthold Goldman, Michel Vasseur)

Date: 23 September 1982

Why is this case famous?

The Dow Chemical is what you could call a senior celebrity. The arbitral award in this case is already in its early 40s. This is one of the classic cases you may hear quoted when seating to arbitrate a Vis Moot panel. But age is not the element that defines the celebrity status of this case, no! This case is famous because it is said to be the origin of the “group of companies doctrine”. Not sure I would use those exact words in a positive remark, though. But one thing is certain: this case made clear that, just because someone did not sign an arbitration agreement, it does not mean that they cannot take part in the arbitration. I know, it sounds controversial when presented like this but wait until you hear the rest of this story.

Family Affairs

This case is not the story of a company, but of a family of companies, and you know how family affairs can fuel the public interest.

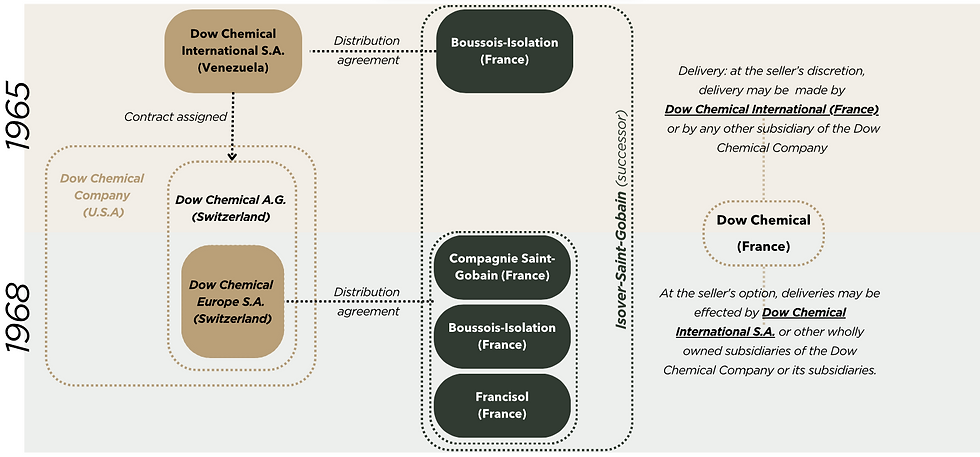

So, we start in 1965, when a Venezuelan company named Dow Chemical S.A. signed a distribution agreement with a French company named Boussois-Isolation for the distribution of various products for the thermal isolation of roofs in France. The Venezuelan Dow Chemical S.A. then assigned that contract to Dow Chemical A.G., a Swiss company who was a subsidiary of the U.S.A based The Dow Chemical Company.

Flash forward to 1968, Dow Chemical Europe S.A., a Swiss subsidiary of the Dow Chemical A.G., signs another distribution agreement, this time with three French companies: Compagnie Saint-Gobain, Boussois-Isolation, and Francisol, also for the distribution of thermal isolation products in France.

Now, this part is important: both the 1965 and the 1968 contracts contained arbitration agreements, as well as provisions indicating that – at the seller’s discretion, deliveries could be made by the French Dow Chemical, or other wholly owned subsidiaries of The Dow Chemical Company or their subsidiaries.

Eventually, the (also French) company Isover-Saint-Gobin succeeded Compagnie Saint-Gobain, Boussois-Isolation, and Francisol in both contracts.

If, like me, you got a bit lost among all those names of companies, here is a scheme to help you visualize the family framework I just described:

Not your ordinary joinder case

You read it right, this is not your ordinary joinder case where a party tries to bring a non-signatory party to the clause to arbitration. Quite the opposite, actually!

In this case, the four “Dow Chemicals” are the claimants to the dispute. A dispute that arose from a series of "incidents" (arbitral tribunal’s word, not mine) involving the use of one of the products distributed under the above mentioned agreements, following which the Dow Group companies were sued. Accordingly, the four companies started an arbitration against Isover-Saint-Gobain, under both distribution agreements, asking to be indemnified in respect of any judgements rendered against them and compensated for material, reputational, and non-material damages.

As you may have already imagined, Isover-Saint-Gobain’s first line of defence here was to say that the arbitral tribunal lacked jurisdiction because there was no arbitration agreement involving neither Isover-Saint-Gobain, nor Dow Chemical (France) or Dow Chemical Company (U.S.A).

Far from trying to bring to arbitration a non-signatory party who does not want to take part in it, this is case is about a non-signatory party who not only wants to be in the arbitration, but started it!

On 12 November 1981, the arbitral tribunal decided to bifurcate the arbitration and address the jurisdiction plea in the first part of the proceedings. Less than a year later, on 23 September 1982, the arbitral tribunal issues an interim award.

The arbitral tribunal’s interim award

The arbitral tribunal started by defining the applicable legal framework, which in their view included French law and the ICC Rules of Arbitration.

Then, the arbitral tribunal pointed out to evidence that Dow Chemical (France) and The Dow Chemical Company (U.S.A) had been part of the negotiations and commercial relations with the companies whose rights Isover-Saint-Gobin succeeded. Some of the examples include:

Exchanged correspondence in which Dow Chemical France negotiated and acted as the seller even before the conclusion of the 1965 distribution agreement.

The fact that Dow Chemical Company (U.S.A) was the owner of the trademarks covering the products sold and distributed.

Correspondence dated 1967 in which Dow Chemical (France) discusses with Saint-Gobin a draft of the new distribution agreement, which includes Dow Chemical Company (U.S.A) as the seller.

Evidence of the parties’ discussions regarding the eventual need to change the seller to the contract for “strategic reasons” (my words, let’s leave at that).

Upon examination of the evidence, the tribunal concluded that:

neither the “sellers” nor the “distributors” attached the slightest importance to the choice of the Dow Group company that would sign the contracts.

In addition to the contract negotiation, the arbitral tribunal also looked at contract performance. From that perspective, the arbitral tribunal deemed relevant, for instance, that:

Deliveries could be performed by other companies form the Dow Group.

The distributor had turned to Dow Chemical (France) to establish the prices when requesting special treatment for its customers.

Dow Chemical (France) carried out the tasks assigned to the seller.

It was Dow Chemical (France) to write the letter of termination of the distribution agreement, which was confirmed effective by Saint-Gobin’s representatives.

Finally, the arbitral tribunal looked into the reality of group of companies. Now, this may be one of the most quoted phrases from this award, where the arbitral tribunal said:

Whereas a group of companies possesses, despite the separate legal personality belonging to each of them, a single economic reality which the Arbitral tribunal must take into account when deciding its own jurisdiction (…).

For those reasons, the arbitral tribunal declared to have jurisdiction over the dispute, despite two of the claimants’ not being de facto signatories to the arbitration agreements.

The aftermath

Isover-Saint-Gobin was not happy with the decision and went before the French courts asking for this interim award to be setting aside. The Paris Court of Appeals rejected the application.

The group of companies’ point

Just before I end this post, I want to leave something here for thought. As I said in the beginning of this story, many refer to the Dow Chemical case as the origin of the group of companies doctrine. I find that difficult to agree with, mostly because Dow Chemical indeed is not your ordinary joinder case, but also because the groups of companies doctrine can be quite controversial when you get into the details of it.

In any case, if you are looking for more information on this, I recommend a great article written by Bernard Hanotiau and Leonardo Ohlrogge published on the ASA Bulletin in 2022 titled “40th Year Anniversary of the Dow Chemical Award” where they discuss the correlation between Dow Chemical and the group of companies doctrine from a very interesting perspective. Go check it out!

Comments